By Cyrus Schayegh

The massive explosion in the port of Beirut on August 4, 2020, has gone down as a landmark date in contemporary Lebanese history. There was the immediate shock of it all: the sound and fury of the explosion and its blast wave that killed at least 218 people, the devastated port and 15 US$ billion worth of property damages in Beirut. Soon the Lebanese classe politique infuriated the country for refusing to take responsibility. There were the devastating longer-term effects on Lebanon’s economy, which went from very bad to extremely bad. And there was a sad symbolism: The port, the beating heart of Beirut’s seemingly unstoppable rise from the late 1800s to around 1970 as a premier economic, infrastructural, and cultural hub linking the Middle East to the world - had literally exploded.

It was not the outcome Beirut imagined. This text outlines how following World War II, the city’s large middle and upper classes supported the building of Beirut International Airport - location code BEY - as a new bridge that, together with the port, would allow Beirut to link political blocs, civilizations, and continents and help their city stay wealthy in the process.

BEY was envisioned even before Lebanon’s independence, from the early 1940s. The planning started in 1945, its construction began in 1947, one year after Lebanon became independent from French rule; and it opened for business in 1950. The new airport covered an area of about three square-kilometers and was located about seven kilometers to Beirut’s south, replacing a much smaller airport built in the late 1930s closer to Lebanon’s capital. It was by area the largest airport in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and almost immediately became its premier airport. It was home to no less than three airlines, including the region’s largest, Middle East Airlines (MEA), which was founded in 1945 and allied with British Overseas Airways Corporation (now British Airways) as well as with Pan American World Airways (Pan Am). And it was the airport used by the largest number of regional airlines and a hub for the transcontinental routes of other airlines including BOAC, Pan Am, Air France, KLM, Air India, Qantas, and a dozen others.

BEY affected the capital so deeply that Beirut became an aerocity: not just a city with an airport, but a city whose self-image was shaped by it.[1] This development renewed the significance of communication and transport infrastructures, historically symbolized by the city’s port,[2] for Beirut as the mashriq’s global hub. Beirut's transformation into an aerocity manifested in several ways, including urbanism, the cityscape, and social relations.[3] This essay focuses on culture. Crucial here was especially middle and upper class Beirutis’ perception of their city as the hub linking East and West. They imagined aviation in Beirut as quintessentially global—a perception that systemically built on, and extended into the postwar world, earlier views of Beirut’s centrality as a world hub.

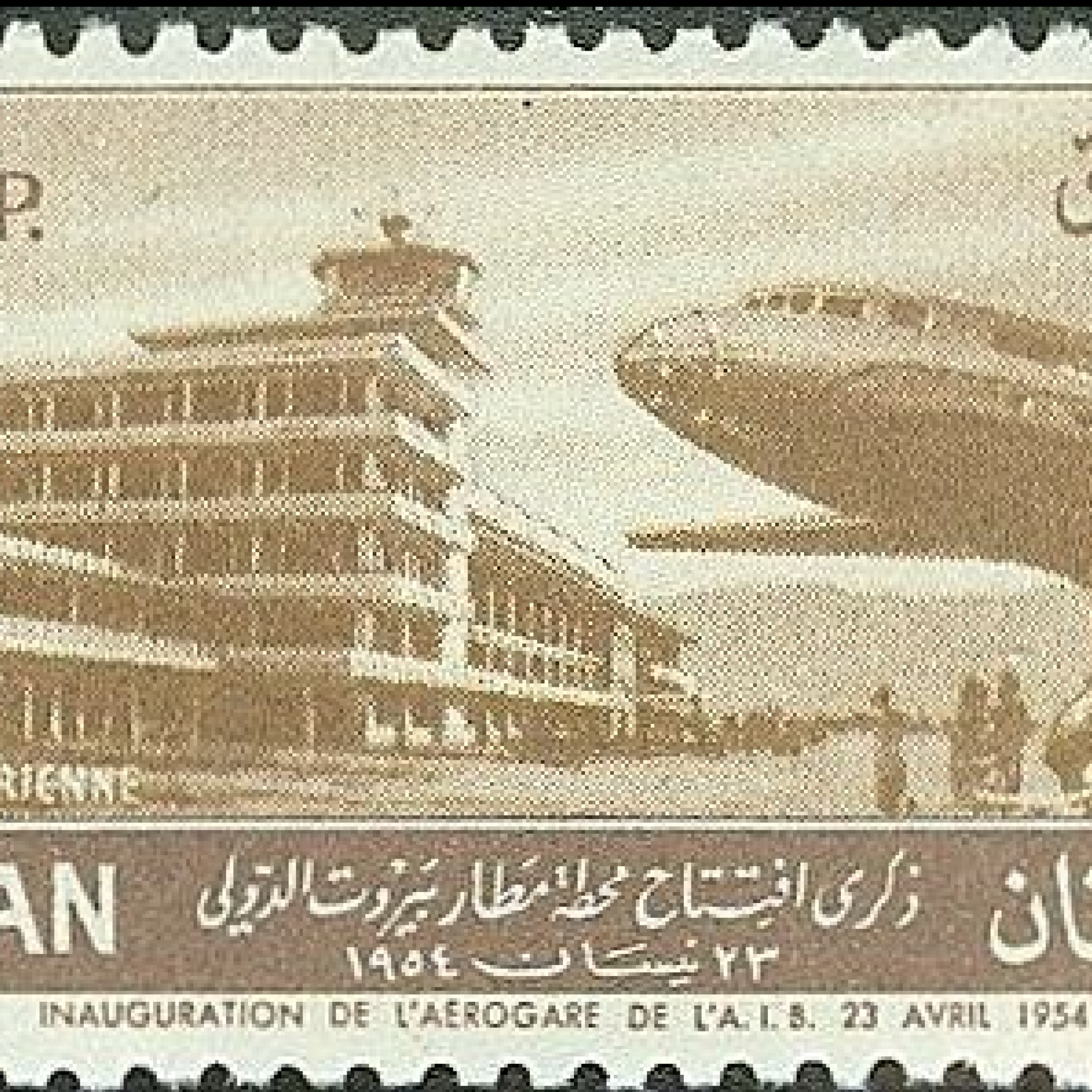

The terminal

To many commentators, BEY's “ultramodern” terminal building, “the most modern and beautiful airport building of its kind in all the East” represented the future.[4] Interesting in this context is an initial concept of the urbanism exhibition that Swiss urbanists Ernst Egli and Rolf Meyer, in Beirut from 1947-52 and 1949-51, respectively, and their Lebanese colleagues mounted in 1950 in Beirut. It presented BEY as the first physical manifestation of Beirut’s and, more generally, Lebanon’s future. As the imagined presenter, a Lebanese living in Lebanon, shows his brother, visiting from the diaspora, around the exhibition, he tells him: “Do not believe these are only projects. Some things have already been realized. … You will soon return home, but you will come back soon. You will return to this new airport that you have already noticed―OUR LEBANON WILL THEN BE TRANSFORMED.”[5]

BEY’s terminal was also about Beirut present, though. Here, the world and Beirut met—literally. The terminal linked Beirut, often referred to as the Paris of the East, to the world’s presumably most refined, i.e. French, savoir-faire by virtue of its architect-designers being the same Parisian bureau who had built Orly Terminal in Paris (1932). Moreover, the airport offered foreign passengers a repackaged version of Beirut: The Bristol, a five-star Beiruti hotel opened in 1951, launched four restaurants in the terminal—among the “most lucrative and modern ones.”[6] The terminal also boasted a 1,000 square-meter duty-free Suk international whose 39 shops were designed especially for transit passengers unable to visit the city: an imaginary tourist version of “Beirut” was brought to BEY’s terminal.[7]

Beirut, the World Connector

Aviation also helped shape Beirut as an aerocity socio-culturally in public events. In 1945, to inaugurate Middle East Airline’s approaching official launch, the MEA leadership including Salim Salam, Chairman and CEO of MEA in the 1980s, and Technical Director Fawzi Hoss, a trained pilot, invited political and media grandees like Mouhieddine Nsouli, director of the newspaper Beirut, and Georges Naccache, director of daily L’Orient, to an “avant-première” at Beirut’s old airport, Bir Hassan.[8] In 1946, Air France flight demonstrations attracted droves of spectators.[9] In 1948, Public Works Minister Gabriel Murr launched BEY’s construction phase with a major on-site celebration attended by scores of diplomats and political and religious dignitaries.[10]

BEY’s 1950 inauguration was “exceptional… From 7AM, a never-ending procession of cars brought to the sands of Khaldé, the site of the new airport, all of Beirut: officials, diplomats, deputies, representatives of the worlds of commerce, finance, press, transport, and a mass of invitees and spectators.” As part of the inauguration, maiden landings were performed by two Air France and Pan Am aircraft; Lebanese Air Force planes made a show; some guests took a local tour by air; and eventually, masses of children and adults rushed the runways. It was “in an atmosphere of all-round cheerfulness that the Lebanese President El-Khoury cut the ceremonial ribbon on the aircraft taxi field, then moved, followed by his official retinue, to a large buffet to toast to Beirut Airport and Lebanon’s prosperity.”[11] The terminal building inauguration in 1954 was, if anything, an even bigger public celebration. It involved representatives of foreign aviation administrations, and “the Civil Aviation directors of various countries, official personalities, and a great multitude of people,” and was again “under the high patronage of the Head of State,” Camille Chamoun.[12] And in 1955, a festival co-organized by the Civil Aviation Directorate and the Air Force demonstrated “the progress in aviation interests:” a “grand success,” it drew over 2,000 spectators to the airport.[13]

A trademark of such public events were speakers and reporters arguing that the airport reflected and deepened Beirut’s role not simply as a regional-global hub but as a world connector. Embraced by middle- and upper-class Beirutis, this view was expressed quite literally, to take one instance, in the influential book Le Liban d’aujourd’hui, Lebanon Today, (1949) by Michel Chiha. A leading banker, ideologue of the hardcore liberal Cénacle libanais, an intellectual center and publication, Chiha was the owner of Beirut’s francophone newspaper Le Jour, and the son-in-law of independent Lebanon’s first president, Beshara al-Khuri. He argued that “situated at the meeting point of three continents, we are obviously an ideal bridgehead and an observatory of the world.”[14]

In public events involving airplanes, this view found expression for example in 1947, when Commerce du Levant, Beirut’s leading economic newspaper, stated that BEY would strengthen Beirut’s role not only as the pivot of the Middle East but also as the crucible where the West blends harmoniously with the East.[15] Similarly, in 1950, a lead article on BEY’s inauguration argued that as this airport would certainly become one of the “world centers of air traffic” and the “indispensable port of call” for all planes flying West to East, the city of Beirut would direct the flow of people not only between Europe and Asia but also the Americas, Africa, and the Orient. BEY, “the Middle East’s aviation pivot,” made Beirut the “bond between the four continents.”[16] In this sense, others added, the airport was to contemporary Beirut what the port had been to the city for decades before, from the late 1800s.[17] The leading Beirut-based airline, MEA, could not resist using this trope in its ads, playing with, and reversing, the opening line of British author Rudyard Kipling’s famous “Ballad of East and West.”

Being in or en route to Beirut

Non-Lebanese eventually adopted bits of this framing, too. A six-page 1952 special on the airport by Beirut’s new Anglophone Daily Star, titled “Where East Meets West,” opened with an account penned by a “traveler who has come to stay,” who attested that only in Beirut can one “engage in furious mental activity … or just laze,” that is, be stereotypically Western or Eastern.[18] And in the late 1950s Robert Miller, a Beirut-based Pan Am employee and occasional writer for the airline’s bi-monthly in-house magazine Clipper, opened a column titled “Beirut News”―Beirut was the only Pan Am station in MENA regularly featured in a Clipper column―as follows: “Beirut kissed by the Mediterranean, crowned by the snow-capped mountains of Lebanon, crossroad of the Occident and Orient … .”[19]

The text was doubly interesting: “… home sweet home to many Pan Americanites, as Pan Am employees were called, [Beirut] is noted for its tremendous hospitality. … Beirut offers attractions to the over-niter and long termer alike as recent Pan Am visitors will agree.” Pan Americanite Beirut was a home indeed, but a particular one: often temporary and visited by other Pan Am employees. Reporting their movements across dozens of Pan Am stations worldwide―an in-station promotion here, a quick visit or a move to another Pan Am station there―was a Clipper staple. Amusing if Orientalist was this note: “Sue Morehouse has placed an order for camel saddles [in Beirut]. It is also known that she purchased several pairs of samurai stirrups in Tokyo. This must mean something. Perhaps she’s planning to ride down the streets of San Francisco in a Lady Godiva-type costume. Our beanies are always up to something interesting.”[20]

More typical was this 1958 BEIRUT NEWS section: “Our new member of the Sales Office staff is Allia Malouf from Massachusetts. A Ticket Agent with TWA for the past six years, Allia decided to substitute Beirut for Boston. … Among the many colorful vacation trips which our Sales people are taking, one of the most promising is that of Roger Khawan who leaves for Brazil. … You, our fellow Pan Am workers, come to Lebanon and we promise you the best vacation ever.”

If “over-niters and long termers” were terms particular to Pan Americanite Beirut, they reflected and formed part of broader trends, too. There was a deepening cultural sense, certainly among the capital’s educated middle and powerful upper classes, that aviation was helping Beirut to accelerate and become more connected than before―helping them, that is, while deepening the chasm between them and Lebanon’s poor and the city's peripheries.

This shifting socio-cultural reality was mirrored in, and its perception was shaped by, the press. Thus, the Daily Star featured a “Personals” section that related who is at present “in” and who “en route” to Beirut, providing gossipy social snapshots that continued prewar, and paralleled postwar, newspaper accounts about famous people arriving by ship in the city.[21]Al-Hayat habitually published photos especially of Lebanese and other Arab dignitaries arriving at BEY (Image 3), and Beiruti dignitaries were interested in photos showing them leaving Beirut by plane.[22] These photos in effect staged BEY as Beirut’s gateway to the world: hypermodern - a plane was always in the photo - and an indelible part of the city.

Meanwhile, Commerce du Levant launched two new permanent aviation-related sections, “Chronique aérienne” in 1947 and “Aviation” in 1952, asking airline companies to deliver more up-to-date flight information so that the fast-changing aviation-driven world of Beirut would remain up-to-date.[23] Furthermore, Beiruti newspapers in the 1940s-50s published literally thousands of airlines ads. (There were many more than ship ads, though, crucially, these continued, too, and newspapers kept publishing daily updates on ship movements.[24]) The airline ads included some that invoked the need for speed,[25] or featured a globe or even a map of an airline’s global route network[26] or a drawing of latest aircrafts.[27] Many years’ and newspapers’ worth of ads and columns helped shape how readers thought of Beirut’s global position[28]―a development that sometimes could have a surprising material-cultural consequence. In 1953, Pan Am’s Clipper related this story about its yearly calendars, 8.5 million copies of which were at the time produced for global distribution: “With a few exceptions delivery of the calendar is routine. One of the exceptions is the Middle East. Somehow hundreds of the calendars disappear before they reach the Pan Am office in Beirut. Before Pan American can hang them on its own walls there, pictures cut out of the stolen calendars are on sale in the bazaars in Beirut. They are framed and sell for around $10 per picture. As Pan American begins to distribute calendars to its business associates in the city, this price gradually drops. Pictures from the calendars are also sold in the bazaars of Damascus.”[29]

Conclusion

Barely two decades after BEY’s opening, on December 28, 1968, explosions shook the airport that, though different from the one devastating the port and Beirut in 2020, formed a turning point in modern Lebanese history, too. That day, an Israeli commando raiding BEY blew up 14 airplanes belonging to three Lebanese airlines, among them MEA, in retaliation for an attack two days earlier by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine on an Israeli El Al airplane in Athens that killed an Israeli passenger. In hindsight, this raid not only heralded increased Israeli intervention in Lebanon, which would peak in the 1982 invasion that led to the evacuation of the Palestine Liberation Organization to Tunis and claimed at least 19,000 lives. It also marked the beginning of the end of Beirut’s role as a key Middle Eastern global hub. Sure, BEY remained open for much of the 1975-1991 civil war and thereafter was modernized. But both the airport and Beirut are shadows of their former selves. When Lebanese are asked to think of the airport positively now, their reaction is nostalgia for years that even to today’s many poor seem like a golden age.[30]

Cyrus Schayegh has been Professor of International History at the Geneva Graduate Institute (IHEID) since 2017. Before, he was Associate Professor at Princeton University and Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut (2005-2008). His recent works include The Middle East and the Making of the Modern World (Harvard UP, 2017), a monograph; Globalizing the U.S. Presidency: Postcolonial Views of John F. Kennedy (Bloomsbury, 2020), an edited volume; and a collection of translated primary sources (Wilson Center Digital Archive, 2023): https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/essays/international-dimensions-decolonization-middle-east-and-north-africa-primary-source. Presently, he is inter alia writing an introduction to, and editing two volumes on, transimperial history, and publishing a series of articles on aviation in postwar Beirut.

[1] Nathalie Roseau, Aerocity : Quand l’avion fait la ville (Marseille: Parenthèses, 2012).

[2] Yasar Ozveren, “The making and unmaking of an Ottoman port city: Nineteenth century Beirut” (PhD diss., SUNY, 1990); Schayegh, The Middle East and the Making of the Modern World (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2017).

[3] I am covering these dimensions in a journal paper, currently under review.

[4] “Aérogare de Khaldé,” CdL 24 April 1954.

[5] “Exposition d’urbanisme,” panels 9&15, in Hs 1413-122.1, Fond Rolf Meyer, ETHZ Archiv.

[6] “Ams dashshana al-ra’is Sham‘un matar Beirut,” al-Hayat 24 April 1954.

[7] “Jawla fi binayat al-matar,” Al-Hayat 24 April 1954; “Développement de l’Aéroport,” CdL 16 July 1955.

[8] “Avant-première à l’aérodrome,” L’Orient 15 December 1945. A Syro-Lebanese aero-club had been founded in 1923, and, relatedly, a school in Rayak trained a few Lebanese.

[9] “Deux avions de tourisme français à l’aérodrome de Beyrouth,” L’Orient 22 October 1946.

[10] “Inauguration,” Commerce du Levant [CdL] 14 April 1948.

[11] “L’Aérodrome de Khaldé,” CdL 5 July 1950.

[12] “L’Aérogare de Khaldé,” CdL 24 April 1954.

[13] “Aviation Festival,” Daily Star [DS] 20 September 1955 (first quote); “Lebanese Air Show a Grand Success,” DS 22 September 1955 (second quote).

[14] Michel Chiha, Le Liban d’aujourd’hui (Beirut: Trident, 1949), 16.

[15] “L’Aérodrome de Khaldé en péril!,” CdL 26 April 1947.

[16] “L’Aérodrome de Khaldé,” CdL 1 July 1950.

[17] “Le problème capital de l’équipement hôtelier,” CdL 27 February 1954.

[18] “Beyond Khaldee, an Oasis,” DS 1952 9 July.

[19] “BEIRUT NEWS,” Clipper 16:3 (April 1957): 11.

[20]Clipper 11:7 (1955): 3.

[21] “Personals,” DS 26 August 1952. From 1950, al-Hayat had a similar section, “al-hayya al-ijtima‘iyya.”

[22] “‘Ala matn ta’ira li-khutut ‘Ban-Amirikan’,” al-Hayat 21 July 1950.

[23] “Chronique aérienne” began in CdL 27 August 1947; “Aviation” began in CdL 6 February 1952.

[24] Ads: e.g. “Li-safarikim ila al-Brazil wa-Arjantin,” al-Hayat 15 July 1950. Daily arrivals: e.g. “Harikat al-marfa’,” al-Hayat.

[25] “‘Asr al-sur‘a … Air France,” al-Hayat 24 July 1950; “Hawl al-‘alim fi ayy waqt kan!” al-Hayat 24 June 1951 [KLM].

[26] BOAC ad, L’Orient 24 June 1947; PAA ad CdL 10 January 1948.

[27] E.g. Constellation: al-Hayat 21 June 1951; Comet: DS 9 June 1952.

[28] Arab airlines published more readily in al-Hayat than in Francophone or Anglophone newspapers: e.g. “Qariban jiddan: al-tairan al-urduni,” al-Hayat 22 July 1950; “Air France,” al-Hayat 4 July 1952.

[29]Clipper 9:24 (1953): 8.

[30]https://www.facebook.com/purenostalgia/posts/beirut-international-airport-late-50s-pure-nostalgia/2763660010327875https://popula.com/2018/12/17/my-airport-beirut-international-airport/; https://lebanonpostcard.com/shop/books/old-time-books/pure-nostalgia-by-imad-kozem/.